Stinky Tricks of Parasitism

What’s in the Story?

Taking care of kids is hard work. You have to ensure that they eat enough so they can stay healthy and grow in size. You also do everything you can to help them survive. All of this can take a lot of time and energy. Isn’t there an easier way? Well, in some species of animals, there is. Some animals drop their eggs off in another animal’s nest, for that animal to raise. This is a form of parasitism, called brood parasitism. It may seem risky, but it’s a pretty successful strategy for those parasite parents.

However, the animal that ends up taking care of the eggs gets a bad deal. They spend all of that time and energy raising another animal’s kid, usually at the expense of their own offspring. You might wonder why the new parent (the host) would accept this job. Well, sometimes they can’t help it… they can’t tell the difference between their eggs and the parasite’s eggs. So, what should they do?

One possibility is that the host could become better at spotting the parasite and stop them from sneaking into the nest. Or instead, the host could change their appearance so that the parasite’s disguise no longer works. Either way would help stop the parasite.

But, luckily for the parasite species, they are also evolving. They may evolve better disguises to help them sneak into the nest once again. This relationship can turn into a competition, where each species pushes the other to change and improve over time.

In the BMC Ecology and Evolution article, “Evidence for a chemical arms race between cuckoo wasps of the genus Hedychrum and their distantly related host apoid wasps,” scientists looked at the smells of distantly related brood parasites and their hosts. They were searching for evidence of the hosts changing their smells to escape their brood parasites.

Smelly Insects

In the insect world, most information is communicated through smells. All insects are covered in a waxy outer layer. This layer holds special chemicals that “smell”. The chemicals, cuticular hydrocarbons, are the smelly suspects. They can carry information about age, sex, reproductive status, and even which colony and caste an insect belongs to. These smells are what a colony of insects use to figure out if another insect is part of their colony, or a potential danger. If parasites can mimic this specific chemical smell, they can sneak into a nest.

Sneaking In

Parasites have evolved several ways to copy this chemical smell and gain access to a colony. First, they might have a weak smell overall. If you are less smelly than other individuals, maybe nobody else will notice you. This strategy is called chemical insignificance.

A second strategy a parasite can use is to physically take the smell of the host through grooming. So, in this case, imagine you were to shower at a friend’s house. You would probably smell more like them after using their body wash. This strategy is called chemical camouflage.

A third strategy a parasite species can use is to evolve over generations to have a smell that is similar to the host’s. This is called chemical mimicry. Parasites can use one, two, or all three strategies at once to sneak into the nest of their hosts.

Ready, set, evolve!

If the parasite evolves to smell like the host, the host can do two things to try to stop the copycat. They can improve their detection abilities, or they can change their smell. Both strategies can stop the parasite from sneaking into the nest. But that solution might not last forever. The parasite will likely continue to evolve. They may develop an even more similar smell or change their smell to match the host’s new smell. Either of these changes would help them sneak into the nest again. The host may then evolve to detect those differences and then the parasite will evolve a better disguise – see where I’m going with this?

If this keeps going back and forth, this process can turn into an evolutionary arms race. The host and parasite continue to push each other to change. This process is also called coevolution.

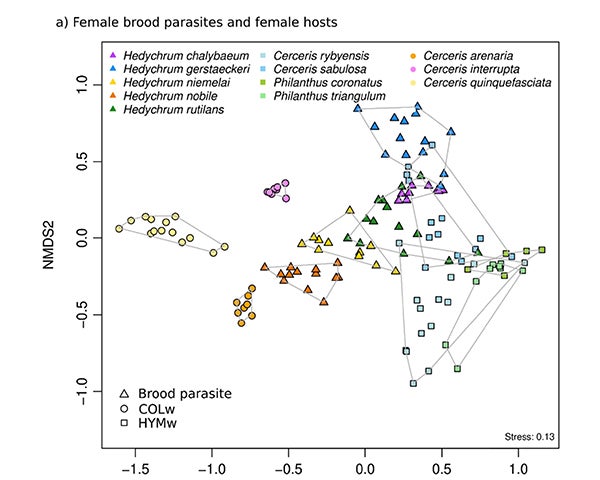

So far, most research has been focused on the first host strategy of improving detection. There has been very little research done on the second strategy of changing their smell. To figure out if hosts do change their smell, scientists studied two distantly related species of wasps along with their brood parasites. They then looked for patterns in their smells. They searched for evidence of hosts changing their smell to avoid being parasitized.

Can wasps change their smell?

Those smelly chemicals mentioned before have two jobs. These chemicals give insects their smell, but they also help stop the insects from drying out.

One of our host species, the bee-hunters, covers their prey in hydrocarbons to keep it fresh, kind of like how we put our food in the fridge. Those smelly chemicals are an important part of their survival. Because of this, bee-hunters can only change their smell a little bit. The other host species, beetle-hunters, does not have this problem. This difference is important. We have one species that can change their smell and another species that cannot, without negative effects.

The researchers thought that because beetle-hunters can change their smell, they would do exactly that. This may mean they are in a chemical arms race with their brood parasites. On the other hand, bee-hunters should be unable to make these changes, and will smell more like their brood parasites.

Imitation is the highest form of flattery

It turns out that the researcher’s hypotheses were correct. Bee-hunters, the wasps that couldn’t change their smell, smelled the same as their brood parasites. But, beetle-hunters, the wasps that could change their smell, did just that. They smelled different from their brood parasites.

This showed us something that we didn’t have a good example of before. Some hosts are using the second strategy to escape parasitism by changing their smell.

As the host smell changed, their parasites also changed. This study gives us a little more proof that these hosts are in a chemical arms race with their parasites. Both species are competing with each other to try to make sure their offspring survive and reproduce.

This back-and-forth arms race is a perfect example of how coevolution can happen. We can all have a bit more appreciation for this process, as it creates the amazing biodiversity we see — or smell! — around us.

Additional images via Wikimedia Commons. Cuckoo and warbler egg image by Roger Culos.

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Stinky Tricks of Parasitism

- Author(s): Victoria Kent

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 16 Apr, 2025

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/plosable/insect-parasitism-mimicry

APA Style

Victoria Kent. (Wed, 04/16/2025 - 12:27). Stinky Tricks of Parasitism. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/plosable/insect-parasitism-mimicry

Chicago Manual of Style

Victoria Kent. "Stinky Tricks of Parasitism". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 16 Apr 2025. https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/plosable/insect-parasitism-mimicry

Victoria Kent. "Stinky Tricks of Parasitism". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 16 Apr 2025. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/plosable/insect-parasitism-mimicry

MLA 2017 Style

One of these don’t belong. Brood parasitism can be found in a lot of different places. Cuckoos are a type of bird that are brood parasites, just like the cuckoo wasps! They lay their eggs in the nest of other bird species, often warblers. The larger eggs pictured here are from cuckoos (the brood parasite) while the smaller eggs are from warblers (the host).

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.