Illustrated by: Sabine Deviche

Have you ever seen small black flies buzzing around your houseplants and wondered what they were? These are most likely fungus gnats (also known as fungus flies). They’re not harmful to humans or pets, but they can be super annoying, especially when there’s a lot of them. In this experiment, you will be using different kinds of liquid traps to catch fungus gnats and to test whether certain kinds of traps work better than others.

Fungus gnats are tiny insects (about 1/8th of an inch long) in the genus Bradysia. They look like fruit flies, but they’re not the same. Fungus gnats reproduce in the moist topsoil of houseplants. It takes three to four weeks for them to complete their life cycle from egg to larvae to pupae to adult. The larvae feed on the fungi, algae, decomposing plant matter, roots, and leaves on the soil surface and in the top layer of soil.

Fungus gnats are not dangerous to people or pets - they don’t carry or spread diseases. But they can be annoying when they buzz around your house. When there are a lot of them, fungus gnats can also hurt the growth of your plants, especially young houseplants that are not big enough to handle larvae feeding on their roots.

There are many different ways to catch and kill fungus gnats. One technique is to use liquid traps. The goal is to lower the gnat population. But there are many different types of liquid traps. Is one better than the others? Let’s find out!

What you need

- Several small jars or open containers

- A small spoon

- Dish soap

- Sugar

- Vinegar, lemon juice, and any other liquids that might “smell tasty” to fungus gnats

- A research notebook or the experiment worksheets

Before you begin

We will be running an experiment to test how different traps work to catch fungus gnats. To do this, we will set out traps near spots where fungus gnats live and count how many are caught per day in each trap. You will use your scientific notebook to record everything about the experiment such as how it is set up, what you think will happen, what you find, and how you could change the experiment in the future. If you don't have a scientific notebook, that's ok! We have a worksheet for you to fill out instead.

Procedure

Step 1: Find a field site. For this, you’ll need to find a spot where fungus gnats live. Fungus gnats reproduce in the moist topsoil of indoor plants, so check around your plants. Describe your field site in your research notebook.

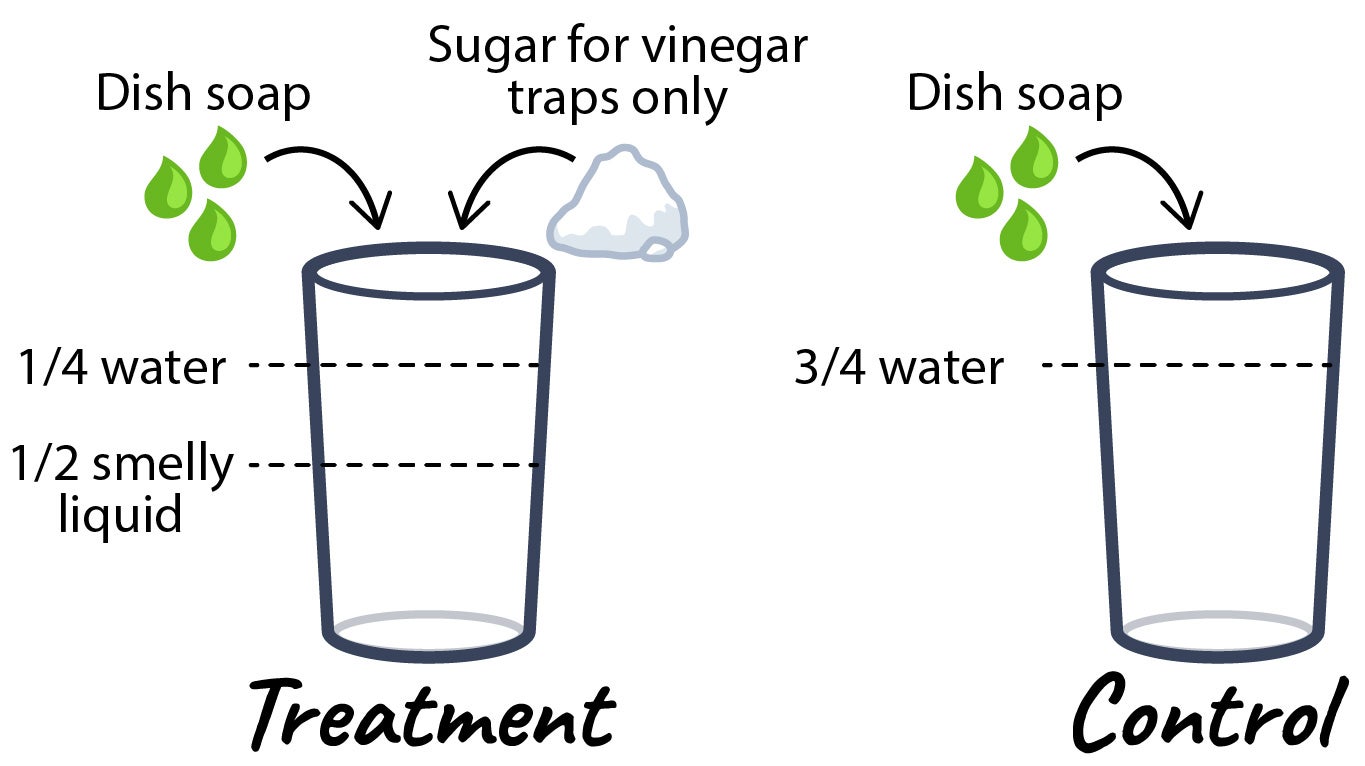

Step 2: Set up the treatment traps. Fill all but one of the jars ½ full of vinegar, lemon juice, or any other liquids that might smell tasty to fungus gnats. For the traps with vinegar, also add a small spoonful of sugar. Then fill each jar ¼ full of water and add two to three drops of dish soap. Stir the traps to dissolve the dish soap (and sugar, for the vinegar trap). The dish soap breaks the surface tension of the liquid in the trap, so that if a fungus gnat likes the smell and lands on the surface of the solution, it will sink and drown. In your research notebook or on your worksheet, record the different treatments you used.

Step 3: Set up the control jar. Fill the last jar or container ¾ full of water. Add two or three drops of dish soap and stir until the soap is dissolved in the water. This will be our “control”. A control is a test with no treatment. The control is meant to show what happens when the treatment does not affect the number of gnats caught. In your research notebook or worksheet, describe your control.

Step 4: Make a prediction and hypothesis. A prediction means guessing what you think will happen in the experiment. Do you think that one kind of trap will catch more fungus gnats than another? Your hypothesis explains why you think you will see certain results. Write down your predictions and hypothesis.

Step 5: Set the traps around the plants in your field site. If possible, the traps should have the same “environmental conditions” or temperature, light, and humidity. We want everything about the traps to be the same except the treatment. That way, if one trap catches more gnats, we know it’s because of the treatment and not something else. Describe the environmental conditions around your traps.

Step 6: You have officially started the experiment! In your research notebook or on your worksheet, write down the day and time that you finished setting everything up.

Step 7: Run the experiment for 1-2 weeks (or more, if you like). Each day at about the same time, count the number of fungus gnats caught in each trap (including the control trap). Record the day, time, and number of gnats caught in each separate trap in your research notebook. Then remove dead fungus gnats with a small spoon. If you need to add water or change the solutions, repeat Steps 2 and 3, and be sure to write this down in your notes.

Tip: Be sure to keep notes of any unexpected results during your experiment. For example, you might catch some other insects besides fungus flies in your traps. Drosophila flies look very similar to fungus flies, except that they have light brown bodies and red eyes. Fungus gnats have black bodies and black eyes. Drosophila flies are also a little bit bigger than fugus flies.

Step 8: Review your data. At the end of the experiment, make a table of your results if you aren't working on one already. Create a column for the day number and for each trap (including the control trap). Then, create a row to collect the data for each new day, like the example below.

On the first day in the table above, we caught 3 fungus gnats in the vinegar trap, 1 fungus gnat in the lemon juice trap, 2 fungus gnats in the soy sauce trap, and 1 fungus gnats in the control trap.

Next, find the total fungus gnats caught for each trap type. To do this, add up the number of fungus gnats caught each day for each trap type. Record this in your research notebook. In the example above, we caught a total of 10 fungus gnats with the vinegar trap, 7 with the lemon juice trap, and 6 with the soy sauce trap.

Step 9: Now, analyze your results. Did one type of trap work better than the others for catching fungus gnats? Why do you think that this might be? And what could you do to make the experiment better? Write down the answers to these questions in your notes.

Step 10 (optional): Communicate your results. Present your findings to the class. If there are several groups, did everyone get similar results? If not, what might explain the difference? You can choose additional formats and share your results. Some options might be: a newspaper or magazine article, illustrated infographic, scientific article, blog post, or social media post.

Dr. David W. Shanafelt is a researcher at the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment (INRAE), one of national research organizations in France. He works on problems in ecology and economics, including the management of natural resources, ecosystem services, and forests.

Photo of fungus fly by Andy Murray via Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: Fly Trapping Trials

Bibliographic details:

- Article: Fly Trapping Trials

- Author(s): David W. Shanafelt

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: 8 Apr, 2025

- Date accessed:

- Link: https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/experiments/fly-trapping-trials

APA Style

David W. Shanafelt. (Tue, 04/08/2025 - 15:03). Fly Trapping Trials. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved from https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/experiments/fly-trapping-trials

Chicago Manual of Style

David W. Shanafelt. "Fly Trapping Trials". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 Apr 2025. https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/experiments/fly-trapping-trials

David W. Shanafelt. "Fly Trapping Trials". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 08 Apr 2025. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. https://live-aab-ws2.ws.asu.edu/experiments/fly-trapping-trials

MLA 2017 Style

Fungus gnats are tiny insects (about 1/8th of an inch long) in the genus Bradysia. They can sometimes be found around houseplants.

Be Part of

Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.